Head transplant…

I’ll say that again… head transplant!

Excitingly the first human head transplant is due to take place this year.

If, like me, you’re a keen fan of extreme surgery attempts, this date will have been in your diary for a couple of years now.

Two years ago, madcap neurosurgeon Dr Sergio Cenavero announced that he planned to carry out the first human head transplant on Russian Valery Spiridonov in the UK this year - calling it ‘Project Heaven’.

But Valery, who suffers from a form of spinal muscular atrophy, has recently been told that he is being dropped from the project in favour of an unnamed man from China.

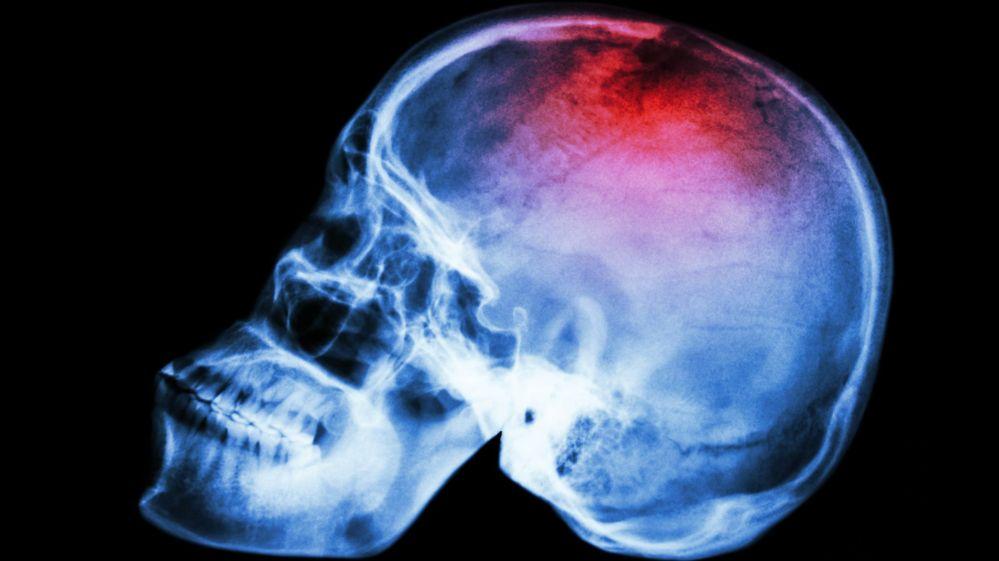

Apparently he’s relieved at this turn of events - and who can blame him. The procedure would have seen his head being cooled to prevent brain cells dying and tubes connected to support key arteries and veins. Then the spinal cord would be cut using a specially designed super sharp scalpel, before being fused onto a donor body using a ‘glue’ called polyethylene glycol to fuse the the spinal cord together.

The muscles and blood supply would be stitched up, before the patient is put into a coma for four weeks to stop them moving while the head and body heal together.

Whilst in a coma, the newly attached head and body would then be subjected to electrical shocks to strengthen the nerve connections. To say that this is risky is a bit of an understatement - it’s the moonshot of surgery. On paper, some of the elements of this have been attempted.

Pioneering scientists have already carried out similar experiments on animals, with varying levels of success. In 1908 Charles Claude Guthrie succeeded in grafting one dog’s head onto the side of another.

And in a huge step forward, during the 1970s, a team of US scientists managed to transplant the head of a monkey onto the body of another. The animal survived for nine days (although some say that is survived for longer and is currently the foreign secretary).

Putting the mind boggling difficulty of attempting such a procedure aside for a moment. The idea of a head transplant throws opens a Pandora’s box of legal, ethical and philosophical considerations. Would having a new body change the patient’s view of themselves?

How would this impact on the patient’s sense of themselves?

Who are we… are we just our minds or does the sense of self include the body?

It is understandable at the most hysterical end of the spectrum to draw parallels with Frankenstein’s Monster or to see something inherently wrong with meddling with the seat of the ‘soul’ in such a way. But perhaps if we look at the idea in a purely objective way - it is no more ethically objectionable than transplanting any major life supporting organ such as a heart, kidney or lung.

And if such procedures pave the way for one day giving paralysed people vastly improved quality of life, isn’t it worth the huge risks involved?

Speaking about the attempt, which he plans to carry out later this year Canavero said it will give us an insight into life after death: “It will be like Gagarin’s flight into space. Gagarin later said he hadn’t seen any angels up there. I want to send another Gagarin beyond the curtain of the unknown and create a situation of clinical death. In our case we’ll be sending a human being to find out what happens to us after we die.”

But I only came in for an ingrowing toenail…